I have a Raspberry Pi 3 with NetBSD 10, running CI jobs. Because SD cards are notoriously unreliable, I attached a USB hard drive to it. The HDD has a swap partition and scratch space for the builds, while root is on the SD. Unfortunately, some writes end up going to the root file system after all, which meant that the SD card was destroyed after only about a year!

So I set out to put the root file system onto the HDD as well, only using an SD card for loading the kernel.

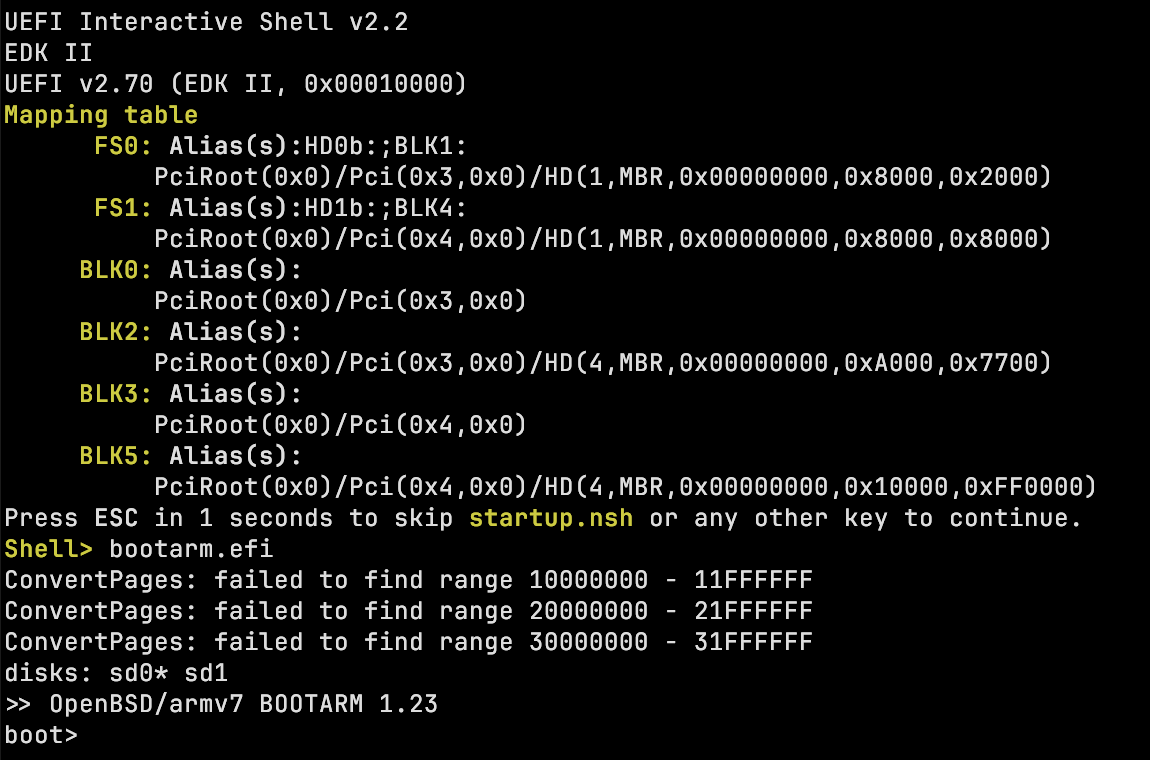

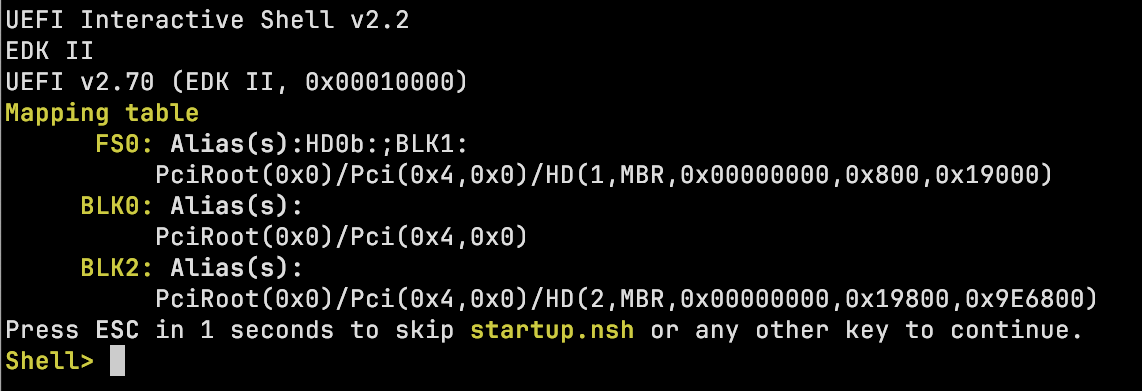

This is an RPi3 running in 32-bit mode with the “classic” RPi bootloader, no UEFI. So it will load config.txt from the FAT partition on the SD card and load the kernel that’s in there. In theory, the cmdline.txt file is supposed to give the root file system, but somehow, changes to this file had no effect (???). But we can force the kernel to use a certain root file system location!

Some theory: disklabels, partitions, wedges

There are two partitioning schemes in use, MBR and GPT.

In MBR partitioning, there is one MBR partition of type NetBSD that contains a disklabel. The disklabel permits splitting the space further, into NetBSD partitions. These are identified by a letter – for example, the a partition on disk ld0 is /dev/ld0a. Usually, a is root, b is swap, and c is the entire disk. As an example, here is the disklabel of my RPi’s SD card:

8 partitions:

# size offset fstype [fsize bsize cpg/sgs]

a: 2459648 196608 4.2BSD 0 0 0 # (Cyl. 96 - 1296)

c: 2656256 0 unused 0 0 # (Cyl. 0 - 1296)

e: 163840 32768 MSDOS # (Cyl. 16 - 95)

In GPT partitioning, there is no disklabel. Instead, there is just a list of partitions. NetBSD partitions, swap, EFI, etc. are directly created as partitions. Partitions have a GUID (that’s why it’s called a GUID partition table) and optionally a label. For example, this is the GPT of the RPi’s hard drive:

# gpt show -l sd0

start size index contents

0 1 PMBR

1 1 Pri GPT header

2 32 Pri GPT table

34 32734 Unused

32768 163840 1 GPT part -

196608 838860800 2 GPT part - rpi3-root

839057408 134217728 3 GPT part - rpi3-swap

973275136 980249999 4 GPT part - scratch2

1953525135 32 Sec GPT table

1953525167 1 Sec GPT header

As an additional complication, the kernel will create wedges for each GPT partition. These are numbered dk devices. Numbers are assigned in the order in which partitions are discovered:

[ 5.463320] dk0 at sd0: "8e1462a7-d2f5-431c-a8f8-9165d455f631", 163840 blocks at 32768, type: msdos

[ 5.473321] dk1 at sd0: "rpi3-root", 838860800 blocks at 196608, type: ffs

[ 5.483322] dk2 at sd0: "rpi3-swap", 134217728 blocks at 839057408, type: swap

[ 5.483322] dk3 at sd0: "scratch2", 980249999 blocks at 973275136, type: ffs

As you can probably imagine, relying on these wedge numbers is brittle: today, /dev/dk0 might be the root, tomorrow you might have some other device plugged in on boot, so dk0 is something else. Thus, NetBSD allows you to refer to them by name (= label) – yes, the terminology is inconsistent. The syntax for this is NAME=somelabel and gets resolved to the correct dk device. So your /etc/fstab might contain lines like:

NAME=rpi3-root / ffs rw 1 1

NAME=rpi3-swap swap swap sw,dp

How the kernel finds the root FS

But wait! fstab is only active once the system is booting. Before that, the kernel needs to find the correct root filesystem. By default, it will guess! This is controlled by a line in the kernel configuration file. The GENERIC kernel contains this bit:

config netbsd root on ? type ?

This means that a kernel with the name netbsd will be built, and it will probe for the root FS location and type. You can also provide a location on the kernel command line, by adding something like root=NAME=rpi3-root.

As said above, this didn’t work for me. So I looked into baking the location in to the kernel. The kernel image contains what is called a rootspec, with a syntax that is almost but not quite the one for the root= command line parameter (of course!). You can set the rootspec in the kernel config.

I discovered that dk devices are not allowed in the kernel config – sensible, since their number can change. (Note that the kernel itself supports this.) But how to get a name in there?

According to the cpu_rootconf(9) manpage, the rootconf can be the prefix wedge: followed by the name of the disk wedge. And config supports quoted strings, which are directly passed to the kernel, as root.

Putting it all together

Inside of the NetBSD source tree, I created a new file, sys/arch/evbarm/conf/MYKERNEL. The filename can be anything you want. In it, I just override bits from GENERIC:

include "arch/evbarm/conf/GENERIC"

no config netbsd

config netbsd root on "wedge:rpi3-root" type ffs

The “no config netbsd” line removes the existing root config from GENERIC, so we can have a different one.

You compile this kernel on a machine of your choice by running

$ ./build.sh kernel=MYKERNEL

resulting in netbsd, netbsd.img and netbsd.ub files. AIUI, the file with no extension is used with UEFI, the .ub one with the U-Boot bootloader, and the .img one is for the RPi bootloader. So I copied the .img file to the boot partition, set its file name in config.txt and voilà! The system now boots from the partition on the HDD.